Once, as Arjuna and Shri Krishna were moving through the forest with their companions, Agni, the god of fire, appeared before them in the form of a weakened Brahmin. In the past, a king had performed an extended yajña lasting twelve years, continuously offering ghee into the sacred fire. As a result, Agni had suffered from indigestion. The prescribed remedy for this condition was the consumption of large quantities of animal fat, which could only be obtained from the ferocious creatures inhabiting the Khandava forest. It was for this purpose that Agni approached Krishna and Arjuna.

This episode—known as the Khandava-dahana—is not merely a dramatic moment in the Mahabharata. It is a layered narrative where theology, kingship, ecological symbolism, and civilizational transition intersect. Fire here is not simple destruction; it is cosmic metabolism, restoring balance to a deity who himself sustains sacrifice and life. The forest is not merely a collection of trees, but a liminal zone—teeming with serpents, demons, ascetics, and untamed life—that stands between wilderness and the rise of an imperial capital.

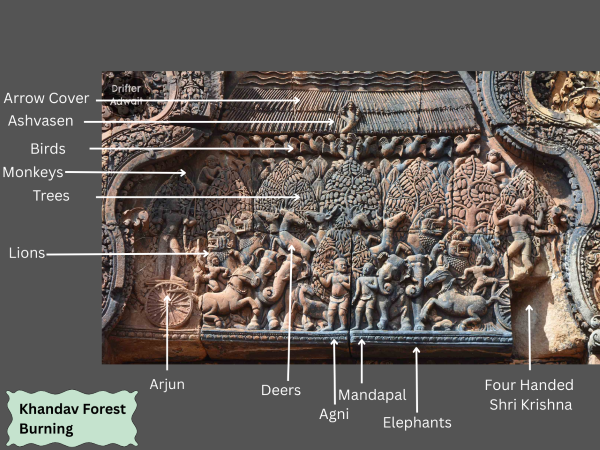

What makes this episode truly extraordinary is that one of its most detailed surviving visual narrations is found not in India, but nearly five thousand kilometers away, carved into the stone gateways of a Khmer temple in Cambodia. In this convergence of Sanskrit epic, Southeast Asian sacred geography, and sculptural mastery, text becomes image, and memory becomes monument.

Agni’s Request and the Bestowal of Divine Weapons

Agni requested Krishna and Arjuna to burn down the Khandava forest so that he might consume the flesh and fat of its beings and thereby regain his strength. The request itself is striking: a god dependent on humans—albeit divine ones—for healing. This inversion underscores a recurring Mahabharata theme: gods and humans are bound by mutual obligation (ṛṇa), and cosmic order depends on cooperation rather than hierarchy alone.

To assist them, Agni brought divine weapons crafted by Vishvakarma himself: a celestial chariot, an immensely powerful bow, two inexhaustible quivers, a formidable mace, and a disc capable of traveling at the speed of thought. Through this event, Arjuna received his famed Kapidhvaja chariot and the radiant Gandiva bow, while Krishna obtained the invincible Sudarshana Chakra and the Kaumodaki mace.

These gifts are not incidental. They mark a turning point in the epic, transforming Arjuna from a heroic prince into a cosmic warrior, and Krishna from a strategist into an openly martial presence. Iconographically, these weapons become permanent identifiers—visual shorthand for divinity and destiny—repeated across centuries of art from Mathura to Angkor.

Armed and prepared, Krishna and Arjuna set out in separate chariots toward the dense forest of Khandava. Using divine weapons and the Sudarshana Chakra, they began to set the forest ablaze. Fierce animals, venomous serpents, and terrifying beings that attempted to escape the flames were struck down by the arrows of Krishna and Arjuna, becoming offerings to the fire. The forest is thus transformed into a vast sacrificial altar, with Agni as both priest and beneficiary.

Indra’s Intervention and a Battle Against the Gods

The Khandava forest, however, was under the protection of Indra, for it was the dwelling place of Takshaka, the serpent king. Takshaka’s presence links the forest to subterranean and chthonic powers—nāgas associated with water, fertility, and hidden knowledge. Indra, as lord of the heavens and wielder of rain, stood in natural opposition to Agni’s consuming fire.

When Indra arrived with his full retinue of gods to defend the forest, the narrative took a startling turn. Krishna and Arjuna—one an incarnation of Vishnu, the other a human hero—stood against the celestial order itself. This confrontation destabilizes simplistic readings of divine hierarchy. The Mahabharata repeatedly asserts that dharma does not always align with institutional power, even when that power is divine.

This cosmic battle is exquisitely depicted on a thousand-year-old temple gateway known today as Banteay Srei. Located in present-day Cambodia, this temple is celebrated for its intricate carvings and narrative density. The sculptor’s ability to translate a complex Sanskrit epic into stone suggests not only technical brilliance but also profound textual familiarity. This was not a vague myth remembered in fragments; it was a living, studied tradition.

Scriptural Correlation: The Adi Parva Descriptions

In the Mayadarsana Parva of the Adi Parva, the Mahabharata describes the scene as follows:

वेगेनाशनिमादायवज्रमस्त्रंचसोऽसृजत्।हतावेतावितिप्राहसुरानसुरसूदनः॥

Indra, the slayer of demons, lifted his thunderbolt and hurled it at Krishna and Arjuna, declaring that the two were as good as dead.

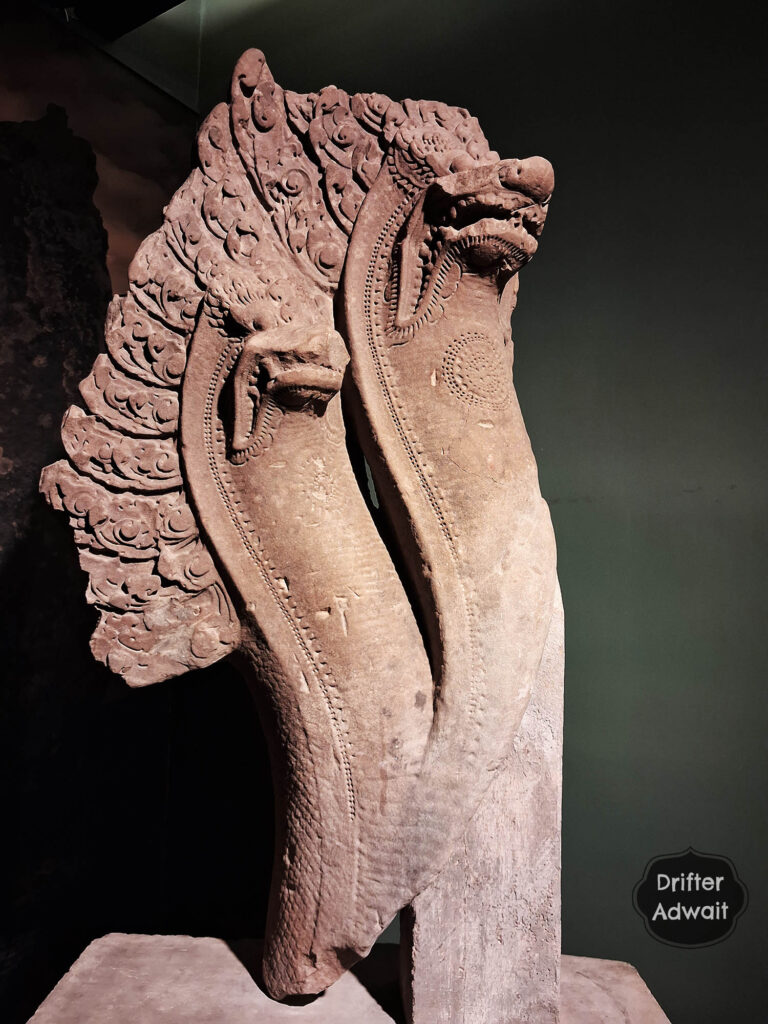

In the sculpture, Indra is shown standing atop Airavata, his celestial elephant, vajra raised in his hand. Airavata’s massive body is adorned with elaborate ornamentation—beaded harnesses, curling tusks, and textured skin—demonstrating the Khmer artist’s mastery over both anatomy and symbolism. Airavata is not merely a mount; he is the embodiment of rain-bearing clouds and royal authority.

Flames, Fear, and the Assembly of the Gods

वहनेश्चापिप्रदीप्तस्यखमुत्पेतुर्महार्चिषः।जनयामासुरुद्वेगंसुमहान्तंदिवौकसाम्॥

तेनार्चिषासुसंतप्तादेवाःसर्षिपुरोगमाः।ततोजग्मुर्महात्मानःसर्वएवदिवौकसः॥

शतक्रतुंसहस्राक्षंदेवेशमसुरार्दनम्॥

As the raging flames rose into the sky, terror spread among the gods. Distressed by the fire, the deities and great sages approached Indra for protection.

In the Khmer sculpture, gods and sages are depicted clustered around Indra with folded hands, their faces etched with anxiety. Crowns tilt, brows furrow, and bodies lean inward, conveying collective fear. This emotional realism is remarkable. Rather than depicting the gods as aloof or omnipotent, the sculptor presents them as vulnerable participants in cosmic crisis—precisely as the Sanskrit text describes.

The Rain of the Gods and Arjuna’s Archery

महतारथवृन्देननानारूपेणवासवः।आकाशंसमवाकीर्यप्रववर्षसुरेश्वरः॥

ततोऽक्षमात्राव्यसृजन्धाराःशतसहस्रशः।चोदितादेवराजेनजलदाःखाण्डवंप्रति॥

Indra unleashed torrential rain upon the burning forest, with clouds pouring water in countless streams.

तस्याथ वर्षतो वारिपाण्डवः प्रत्यवारयत्।शरवर्षेण बीभत्सुरुत्तमास्त्राणि दर्शयन्॥

Arjuna, demonstrating unparalleled mastery of archery, intercepted the rain mid-air with a canopy of arrows.

In stone, this moment is rendered with breathtaking ingenuity. Beneath Airavata’s feet, carved ripples suggest pooling rainwater. Yet the flames below remain untouched, visually separated by a lattice of arrows emanating from Arjuna’s bow. Time, motion, and causality are frozen into a single frame—an achievement that rivals the finest narrative reliefs anywhere in the premodern world.

Animals in Flight and the Chaos of Destruction

द्विपाःप्रभिन्नाःशार्दूलाःसिंहाःकेसरिणस्तथा।

मृगाश्चमहिषाश्चैवशतशःपक्षिणस्तथा।

समुद्विग्नाविससृपुस्तथान्याभूतजातयः॥

Elephants oozing musth, lions, tigers, deer, wild buffaloes, hundreds of birds, and countless other creatures fled in terror.

The sculptural panel translates this catalogue into a swirling vortex of movement. Birds burst upward from foliage, monkeys scramble up trees, lions leap with bared teeth, deer vault mid-stride, and elephants charge with trunks raised. Some animals are crushed beneath hooves, others collide in panic. The forest itself seems alive with chaos, writhing under the onslaught of fire. The fidelity to the textual description is so precise that the sculpture reads almost like a visual commentary on the verse.

Mayasura, Mandapala, and the Rare Warrior Krishna

At the center of the panel, Mandapala Rishi appears pleading with Agni to spare his wife Jarita and their four sons—Jaritari, Sarisrikka, Stambamitra, and Drona. This brief yet poignant episode reminds the viewer that even amid cosmic necessity, individual suffering is acknowledged. Compassion and destruction coexist uneasily, as they often do in the epic.

(Pleading person could be Mayasura, the great architect of the Asuras, who survives the conflagration at Arjuna’s request. His later construction of the Maya Sabha at Indraprastha becomes a direct material consequence of the forest’s destruction—architecture rising from ashes.)

On one side of the relief stands Arjuna in his chariot, bow drawn. On the other is Krishna, four-armed, mounted on a chariot, holding the Sudarshana Chakra and Kaumodaki mace. This image of Krishna as an active warrior is exceptionally rare in Indian art, where he is more often depicted as charioteer or divine counselor. Its presence here underscores the sculptor’s deep engagement with the Mahabharata’s martial theology.

Indra’s Final Assault and Defeat

तत उत्पाट्य पाणिभ्यांमन्दराच्छिखरं महत्।सद्रुमं व्यसृजच्छक्रो जिघांसुः पाण्डुनन्दनम्॥

ततोऽर्जुनो वेगवद्भिज्वलिताग्रैरजिह्मगैः।शरैर्विध्वंसयामास गिरेः शृङ्गं सहस्रधा॥

Indra uprooted a massive mountain peak with trees intact and hurled it at Arjuna. Arjuna shattered it into thousands of fragments with blazing arrows.

Despite relentless effort, Krishna and Arjuna could not be defeated. The gods withdrew when a celestial voice declared:

न च शक्यौ युधा जेतुं कथंचिदपि वासव ।।

वासुदेवार्जुनावेतौ निबोध वचनान्मम । नरनारायणावेतौ पूर्वदेवौ दिवि श्रुतौ ।।

भवानप्यभिजानाति यद्वीर्यो यत्पराक्रमौ । नैतौ शक्यौ दुराधर्षी विजेतुमजितौ युधि ।।

Know this beyond all doubt: Lord Vasudeva and Arjuna are unconquerable in battle. No stratagem, no force of arms, no power born of heaven or earth can prevail against them. They are the ancient and eternal deities Nara and Narayana, whose glory is proclaimed even in the highest celestial realms. Their valor is legendary, their strength immeasurable, and their resolve unshakable. You yourself know the depth of their might. As warriors, they are peerless and invincible, terrible to behold in combat, and there exists no being in any of the three worlds who can vanquish them upon the field of war.

Indra accepted this truth and returned to heaven, granting Arjuna a boon that he would one day receive all divine weapons upon pleasing Mahadeva.

Saved from the Conflagration: Jarita, Her Sons, and Agni’s Compassion

Mandapala was a revered Maharshi who had perfected tapas and lifelong brahmacharya, fulfilling his obligations to the gods and sages through sacrifice and Vedic study. Yet in the Pitrloka he was denied entry, reminded that one debt remained unpaid—the duty to the ancestors through progeny. Accepting this law of dharma, Mandapala returned to earth, assumed the form of a bird, and married Jarita, through whom four sons were born: Jaritari, Sarisrikka, Stambamitra, and Drona.

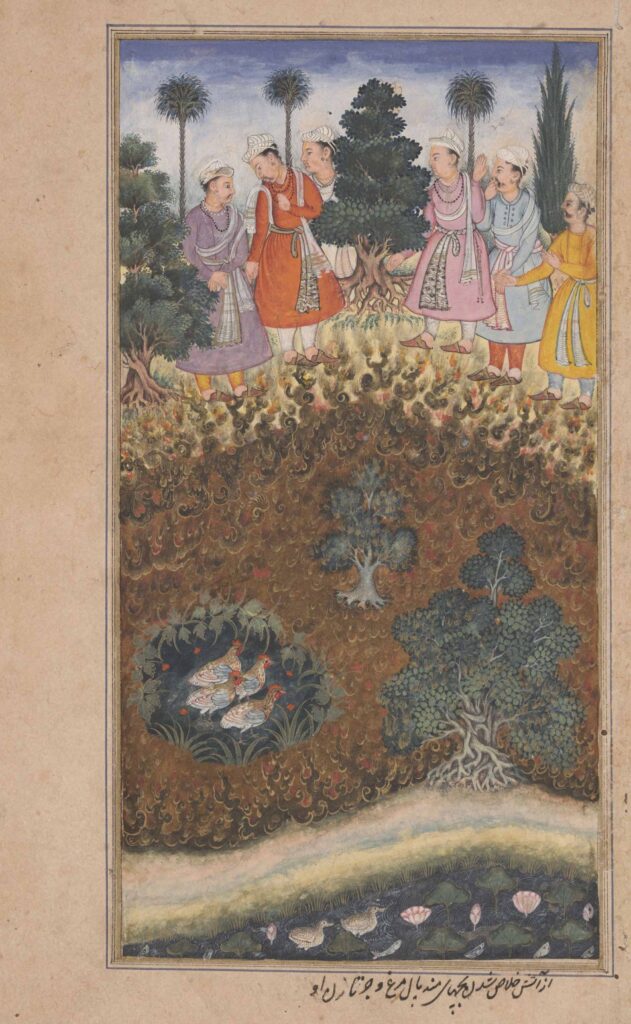

Mandapala later departed, while Jarita and the children continued to dwell in the forest that fate had marked for destruction—the Khandava forest. When Mandapala returned and saw Agni advancing toward it, he understood at once what was to come and hymned the fire-god with deep humility. Pleased by his devotion, Agni promised that Jarita and her four sons would be spared.

As the flames closed in, Jarita resolved to give her life to save her children, but the four sons—born of a great rishi and possessed of innate spiritual wisdom—restrained her and themselves prayed to Agni. Moved by their devotion, Agni opened a righteous path through the inferno, leading Jarita, Jaritari, Sarisrikka, Stambamitra, and Drona safely out of the burning Khandava—an intimate moment of compassion preserved amid cosmic destruction.

Agni’s Fulfillment and the Aftermath

स मांसरुधिरौघैश्च वसाभिश्चापि तर्पितः ।।

उपर्याकाशगो भूत्वा विधूमः समपद्यत । दीप्ताक्षो दीप्तजिह्वश्च सम्प्रदीप्तमहाननः ।।

Thus, having been abundantly nourished by the flesh, blood, and fat of the forest creatures, Agni became fully satisfied. Rising upward and moving freely through the sky, he was freed of smoke and impurity. His eyes shone with renewed brilliance, radiance returned to his tongue, and his vast, open mouth blazed with an overwhelming and resplendent fire.

Mayasura was spared at Arjuna’s intervention and later built the famed Maya Sabha at Indraprastha. Takshaka and his son Ashvasena survived; Ashvasena would later seek revenge during the Karna–Arjuna battle.

Rethinking Khandava-dahana: Historical Context and Moral Time

The Khandava episode does not glorify destruction for its own sake. It reflects the social, political, and philosophical realities of its time. Forests in ancient texts often symbolized disorder and obstacles to structured civilization. The destruction of Khandava was a transitional phase leading to the establishment of Indraprastha—a planned royal capital.

Judging this episode solely through modern environmental ethics risks intellectual anachronism. While deforestation today is undeniably destructive, applying present-day moral frameworks to ancient narratives without context erases history and philosophy alike. Morality is time-bound; responsibility evolves.

Mahabharata Beyond India: A Transoceanic Cultural Memory

That this intricate narrative was carved in Cambodia, long before printing or written manuscripts were widespread, speaks volumes. Epics like the Mahabharata traveled across oceans through memory, oral transmission, and cultural exchange. They were not imposed but embraced—absorbed into distant societies that found meaning, values, and worldview within them.

This extraordinary transmission stands as testimony to the civilizational depth, adaptability, and timeless influence of Indian cultural thought—an influence powerful enough to shape imaginations thousands of kilometers away, without conquest or coercion.

The Khandava Forest burns no longer—but its story, carved in stone and carried across seas, continues to illuminate how civilizations remember, reinterpret, and reimagine their past.

Reference: Aadiparva, Volume 1, Mahabharat, Geeta Press Gorakhpur.

Wow.. Very informative 👍