The Mahabharata does not arrive at its climax with triumphant heroism or righteous celebration. It reaches its end through exhaustion, collapse, and fear. After days of relentless slaughter, when the battlefield had swallowed warriors, ideals, and entire lineages, the war reduced even its greatest antagonist to a man running for his life. The final chapter of Bhima vs Duryodhana is not a tale of victory earned through applause, but of survival wrested from moral collapse — a moment where power, pride, and destiny converge at the very edge of dharma.

This moment forces the Mahabharata’s most unsettling question into the open: what does dharma demand when every righteous path has already been scorched? Dharma here is not abandoned, nor corrupted, but burdened. Krishna and the Pandavas do not step outside righteousness; they step deeper into its cost. When rules themselves begin to protect adharma, dharma must choose responsibility over appearance. The epic does not present this as convenience or cruelty, but as tragic necessity — a reminder that justice, when exercised in the real world, is rarely unblemished, yet must remain conscious, restrained, and accountable.

In Shalya Parva of great epic Mahabharata, Maharshi Veda Vyasa writes,

सनापश्यत्समरेकंचित्सहायंरथिनांवरः।नर्दमानान्परान्दृष्ट्वास्वबलस्यचसंक्षयम्।।

तथादृष्ट्वामहाराजएकःसपृथिवीपतिः।हतंस्वहयमुत्सृज्यप्राङ्मुखःप्राद्रवद्भयात्।।

Meaning:

O King! When Duryodhana, the best of chariot warriors, saw no ally left on the battlefield, heard the roaring of enemies, and beheld the destruction of his army, that lone ruler abandoned his slain horse and fled in fear toward the eastern direction.

This is how adharma finally loses its footing. It does not collapse in a blaze of honor or a final defiant stand, but in silence and retreat. Duryodhana, who once commanded eleven akshauhinis, now had nothing left but breath and fear. He fled, not to regroup, but to hide.

On the last day of the catastrophic Kurukshetra war, news reached Krishna that Duryodhana had concealed himself in a lake. The messenger was an ordinary hunter, a man untouched by royal oaths or battlefield glory, and yet he carried information that would decide the fate of an empire. Krishna did not react immediately. He gathered the Pandavas and walked with them toward the lake, where the water lay strangely still, unnaturally calm. By the power of illusion, Duryodhana had stilled the surface, hoping invisibility would succeed where weapons had failed.

Standing at the lake’s edge, the Pandavas called out to him. Some hurled accusations, reminding him of the dice game, of Draupadi’s humiliation, of Abhimanyu’s merciless killing. Some mocked him, questioning whether this was the courage expected of a Kuru king. Others challenged him directly, attacking the last fortress he possessed — his pride. Gradually, words flowed into argument, argument into provocation, and provocation into destiny. In the course of this exchange, Yudhishthira spoke.

He spoke not with anger, but with the calm confidence of a king who truly believed in giving fair chance. He offered Duryodhana a chance to fight, one against one, weapon of his choosing, with the Pandavas merely watching.

यस्त्वमेकोहिनःसर्वान्संगरेयोद्धुमिच्छसि।

एकएकेनसंगम्ययत्तेसम्मतमायुधम्।।

तत्त्वमादाययुध्यस्वप्रेक्षकास्तेवयंस्थिताः।

Meaning:

If you desire to fight all of us one by one in battle, so be it. Choose the weapon you prefer and fight each of us individually. We shall stand as spectators.

Yudhishthira went further, sealing the offer with a promise that sounded magnanimous, even righteous, but carried unforeseen danger.

स्वयमिष्टंचतेकामंवीरभूयोददाम्यहम्।।

हत्वैकंभवतोराज्यंहतोवास्वर्गमाप्नुहि।

Meaning :

O hero! I grant you this boon again—if you kill even one of us, the entire kingdom shall be yours; if you are slain, you shall attain heaven.

Seventeen days of destruction had brought Bharatavarsha to this fragile edge. Countless women had been widowed, countless children orphaned, and immeasurable wealth lay buried beneath corpses and chariots. Krishna, who had labored relentlessly to ensure that victory remained aligned with dharma, saw that victory suddenly wobble. One sentence, spoken in misplaced generosity, threatened to undo everything.

As Duryodhana emerged from the water, roaring with renewed confidence, Krishna’s restraint finally broke.

एवंदुर्योधनेराजन्गर्जमानेमुहुर्मुहुः।युधिष्ठिरस्यसंक्रुद्धोवासुदेवोऽब्रवीदिदम्।।

Meaning :

Sanjaya said: O King! As Duryodhana roared repeatedly, Lord Vasudeva (Krishna), deeply angered, spoke to Yudhishthira.

Krishna questioned Yudhishthira sharply, asking what would happen if Duryodhana chose any of the brothers except Bhima for combat.

यदिनामह्ययंयुद्धेवरयेत्त्वांयुधिष्ठिर।अर्जुनंनकुलंचैवसहदेवमथापिवा।।

Meaning:

Yudhishthira! If Duryodhana were to choose you, Arjuna, Nakula, or Sahadeva for combat, what then?

He answered his own question with a truth that none of them wanted to hear.

नत्वंभीमोननकुलःसहदेवोऽथफाल्गुनः।जेतुंन्यायेनशक्तोवैकृतीराजासुयोधनः।।

Meaning:

Neither you, nor Bhima, nor Nakula, nor Sahadeva, nor Arjuna can defeat Duryodhana fairly; for King Suyodhana is highly practiced in mace combat.

Krishna explained that while Bhima possessed immense strength, Duryodhana’s relentless practice with the mace gave him an advantage that strength alone could not overcome.

बलीभीमःसमर्थश्चकृतीराजासुयोधनः।।बलवान्वाकृतीवेतिकृतीराजन्विशिष्यते।

Meaning:

Bhima is strong and capable, but Duryodhana is more practiced. Between strength and skill, skill prevails.

His frustration finally spilled over into bitter irony.

एकंवास्मान्निहत्यत्वंभवराजेतिवैपुनः।नूनंनराज्यभागेषापाण्डोःकुन्त्याश्चसंततिः।।अत्यन्तवनवासायसृष्टाभैक्ष्यायवापुनः।।

Meaning:

By saying, “Kill even one of us and become king,” you imply that the sons of Pandu and Kunti are unfit to rule—perhaps created only for endless exile or begging.

Krishna’s rebuke was harsh, but it did not end there. Even as he spoke, his mind was already moving ahead, measuring consequences rather than assigning blame. Krishna never abandoned leela — not playfulness, but the deeper play of steering events without overtly violating dharma. He knew that Duryodhana could not be defeated by fairness alone. To end adharma, dharma itself would have to endure a wound.

Instead of commanding, Krishna chose suggestion. Instead of stopping the duel, he subtly redirected it. By emphasizing Duryodhana’s superiority in mace combat, he touched the one flaw Duryodhana could never overcome — his pride. The implication was clear: Bhima was not worth fearing. Duryodhana heard not caution, but challenge.

Predictably, he chose Bhima.

The circle was formed. Krishna, Balarama, and the four Pandavas sat around the arena, arms folded, legs braced, watching silently as Bhima and Duryodhana prepared for the final duel. The last moments of Duryodhana’s life were about to unfold — moments that, centuries later, would be captured in stone in a distant land, far from Kurukshetra, yet bound forever to its moral universe.

The Duel That Refused to End

The duel that followed did not end quickly. It stretched on, heavy and punishing, like the war itself. Bhima struck with brute force, drawing blood again and again, but Duryodhana endured. Trained relentlessly under Balarama and hardened by years of practice, he absorbed each blow, countered with precision, and refused to fall. Gradually, exhaustion crept into Bhima’s limbs. His breathing grew heavier, his movements slower. Strength alone was failing him.

When Strength Was No Longer Enough

Watching this, Krishna said nothing aloud. He did not shout instructions or halt the duel. Instead, he met Bhima’s eyes and reminded him silently of a vow once taken — a promise made before Draupadi, when her humiliation still burned fresh. The moment hung suspended. Bhima understood.

The Blow That Adharma Could Not Avoid

As Duryodhana leapt into the air, confident, certain that victory was within reach, Bhima lifted his mace and struck where he was never meant to strike. The blow shattered Duryodhana’s thigh. The duel ended not with triumph, but inevitability. The rules of combat had been broken, but adharma had been broken first. Duryodhana fell, not as a coward, but as a tragic figure undone by pride, envy and excess.

From Kurukshetra to Distant Shores

Centuries passed. The dust of Kurukshetra settled, the cries of war faded, and kingdoms rose and fell across the subcontinent. Names that once shook the earth slowly softened into legend, yet the Mahabharata refused to remain confined to time or geography.

It travelled — not carried by conquering armies, nor enforced by political power, but borne quietly through ideas, stories, and moral dilemmas that spoke to human conflict itself. Long before maps marked borders, the epic had already crossed them.

Cambodia, 928 CE: A Kingdom at the Crossroads

Cambodia. The year was 928 CE.

In Angkor, King Yashovarman ruled, but beneath the stability of the throne, dynastic rivalry simmered. Jayavarman IV, though royal by blood, became a victim of this internal struggle and was pushed away from the Khmer capital.

Exile, however, did not diminish him. Like the heroes of the epics he revered, Jayavarman chose creation over resentment. Outside the traditional seat of power, he established a new capital, consciously modeled on Indraprastha itself. He named it Lingapura, known today as Koh Ker.

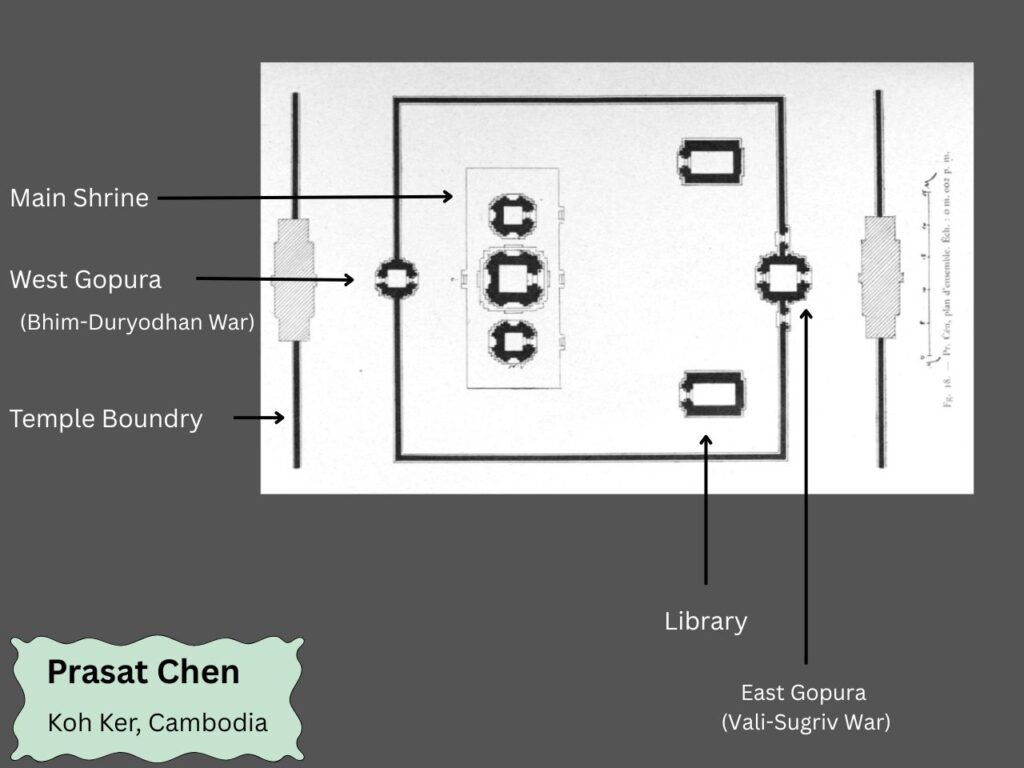

Prasat Chen: Where Epics Guard the Threshold

At the heart of this new capital, Jayavarman commissioned a temple complex called Prasat Chen, built in the trinity style. Yet what made this temple extraordinary was not its layout or scale, but what stood beneath its gopuras.

At the very thresholds — the spaces between inside and outside, sacred and worldly — he placed two monumental scenes. These were not carved into walls or reduced to relief panels. Each figure was fully sculpted, freestanding, and over seven feet tall, demanding engagement from every angle.

Brother Against Brother, Again

One scene depicted the duel between Sugriva and Vali.

The other captured the final moments of Bhima and Duryodhana.

This pairing was deliberate. Both stories center on conflict where the enemy is not foreign, but familial. In both, the struggle is not merely for power, but for legitimacy, justice, and moral authority. Jayavarman, himself wounded by fraternal rivalry, clearly saw his own story reflected in these epics. For him, the Mahabharata was not mythology — it was instruction.

Stone Frozen at the Edge of Sin

In the Bhima–Duryodhana sculpture, the moment chosen is exact and unforgiving. Duryodhana is shown mid-leap, his body tense, confidence still intact. Bhima stands grounded, mace raised, on the verge of delivering the forbidden blow.

Around them sit the Pandavas, Krishna, and Balarama, arranged in a circle. Their arms are folded, their legs braced. Their expressions carry no celebration — only anxiety, restraint, and faith. They know what is about to happen. They know it violates the code of combat. Yet they also know that there is no other way left.

Pic 1: Shri Ram, Phanom Penh Museum, Koh Ker Style, Cambodia

Pic 2: Vali Sugriv Duel, Phanom Penh Museum, Koh Ker Style, Cambodia

Art That Refuses Easy Judgement

What makes this sculpture extraordinary is its moral honesty. The Pandavas are not triumphant spectators. They are witnesses to a moment of unbearable ethical tension. The Khmer sculptors have captured not victory, but hesitation — the exact instant when dharma is weighed against its own consequences.

This is not the breaking of dharma, but its most difficult expression. The rules of combat are strained, not abandoned, as dharma chooses responsibility over appearance. The sculpture freezes that moment forever, compelling the viewer to confront the truth that righteousness is not always clean, but it is always conscious.

When the Mahabharata Became Universal

Such a splendid sculpture does not exist even in India — not at this scale, and not with this narrative courage. Two warriors are locked in violent motion, neither exaggerated nor diminished, frozen at the precise instant where the demands of dharma narrow to a single, unavoidable choice. This is not the collapse of moral certainty, but its final concentration — the moment when all alternatives have been exhausted and responsibility alone remains.

This is not hero worship, nor is it a celebration of violence. It is philosophical art that affirms a hard truth the Mahabharata insists upon: when adharma fortifies itself behind rules, dharma must act beyond comfort, but never beyond conscience. The Pandavas are not witnesses to transgression; they are witnesses to necessity. Krishna’s presence does not sanction wrongdoing — it safeguards intention. The blow that is about to fall is not born of rage or ambition, but of restraint carried to its limit.

What the Khmer sculptors understood with rare clarity is that righteousness is not always symmetrical or gentle. Sometimes it appears as resolve rather than purity. The splendid sculpture does not ask the viewer to feel uneasy about justice; it asks the viewer to recognize its weight. Dharma here does not retreat, compromise, or disguise itself — it accepts the cost of preservation. In capturing this moment, the Mahabharata ceases to belong to a single land or people and becomes universal, because every civilization eventually confronts the same truth: that order survives not by ideal outcomes, but by necessary action taken with full awareness of its burden.

Displacement, Theft, and Homecoming

Over time, many of these sculptures were stolen by traffickers and sold on the international art market for millions of dollars. Their absence left emphasised voids at Prasat Chen, wounds carved into stone.

In recent years, the Cambodian government succeeded in recovering several of these masterpieces. Today, they are no longer housed at the temple itself but are preserved securely in the National Museum of Phnom Penh, protected from further loss.

A Sacred Site Surrounded by Silence

Prasat Chen lies nearly a hundred kilometers from Siem Reap. Though Koh Ker contains hundreds of temples, only about twenty to twenty-five are accessible to visitors today.

The reason is grimly modern. The surrounding forest is still scattered with live landmines, remnants of more recent conflicts. A careless step can still cost a life. The Mahabharata’s violence, it seems, has echoed across centuries in ways no sculptor could have foreseen.

What Jayavarman Understood About Dharma

Jayavarman IV would eventually reclaim power and rule the entire Khmer empire, much like Yudhishthira would ascend the throne after unimaginable loss. But perhaps his greater achievement lay not in political victory.

By placing these sculptures at the temple’s threshold, Jayavarman acknowledged a hard truth: dharma is not about easy choices. Justice often demands standing against one’s own blood. Sometimes, to protect order, rules themselves must bend.

Why This Sculpture Still Echoes in India

Vali and Duryodhana were mighty, capable, and in many ways deserving. Yet both failed the final test of dharma, or restraint. Their defeats came through rule-breaking blows, but those blows were unavoidable.

That this moral complexity — this refusal to sanitize victory — travelled from India to Cambodia without force or conquest is India’s quiet civilizational triumph. In Koh Ker, the Mahabharata did not remain Indian; it became universal.

When stone speaks there, it speaks of India’s deepest truth:

that dharma survives not through purity, but through responsibility, and that sometimes, standing for justice means standing alone.

References:

1. Volume 4, Mahabharata Geeta Press Gorakhpur, India.

2. UNESCO, Koh Ker: Prasat Chen and its sculptures

3. HelloAngkor, Prasat Chen Temple