यो जरत्कारुणा जातो जरत्कारी महायशाः ।

आस्तीकः सर्पसत्रे वः पन्नगान् योऽभ्यरक्षत ।

तं स्मरन्तं महाभागा न मां हिंसितुमर्हथ ।।

“He who was born of Jaratkaru and Jaratkaru, the noble Astika who halted the serpent sacrifice – I remember him now. O blessed serpents, do not harm me.”

Long before antiseptic sprays and anti-venom vials, protection from snakebite in rural India often came in the form of a mantra—murmured under the breath, passed down through generations. It was not a spell of fear but a chant of memory and reverence.

In villages, particularly in Maharashtra, this protective snakebite mantra was recited while walking through thick undergrowth, tall grasses, or while grazing cattle. Its roots run deep into the soil of Hindu mythology, anchored in a dramatic saga of betrayal, divine intervention, cosmic duty, and the power of a single child to change destiny.

But who was Astika, and why does the very memory of his name keep snakes at bay?

Let us journey into one of India’s most powerful and rarely told legends.

The Tale Begins: A Horse, A Lie, and a Terrible Curse

The story begins not in war or chaos, but in a petty household argument—between Kadru and Vinata, two wives of the ancient sage Kashyapa, and mothers of celestial beings.

One day, as the two watched a divine horse graze in a field, a strange debate arose.

Kadru claimed that the horse’s tail was black.

Vinata insisted it was white.

Their egos tangled quickly, and they wagered:

“The one who is proven wrong shall become the other’s slave.”

To win, Kadru hatched a deceitful plan. She instructed her sons—the serpent nagas—to go and hang on the horse’s tail, making it appear black.

But many of the serpents, noble in spirit and unwilling to lie, refused.

And so Kadru, their own mother, cursed them.

Her words burned through the heavens:

“You shall perish in the great Sarpa Satra – the serpent sacrifice that shall be performed by a king of the Kuru dynasty. You shall be cast into sacred flames, and none shall survive.”

Among these cursed nagas was Vasuki, who would one day be king of serpents—and the future brother-in-law of a certain sage named Jaratkaru.

The Cosmic Churning: Vasuki Endures for the Universe

Years rolled by, and the world moved toward another grand event—Samudra Manthan, the churning of the ocean of milk. The gods and demons, needing a rope strong enough to churn the vast ocean, turned to none other than Vasuki.

He was wrapped around Mount Mandara, used as the churning rope itself.

मन्धानं मन्दरं कृत्वा तथा नेत्रं च वासुकिम् । देवा मधितुमारब्धाः समुद्रं निधिमम्भसाम् ।।

अमृतार्थे पुरा ब्रह्मस्तथैवासुरदानवाः । एकमन्तमुपाश्लिष्टा नागराज्ञो महासुराः ।।

विबुधाः सहिताः सर्वे यतः पुच्छं ततः स्थिताः ।।

-Thus, in ancient times, the gods and demons came together to churn the cosmic ocean in search of Amrit—the nectar of immortality. They used Mount Mandara as the churning rod and the mighty serpent king, Vasuki, as the rope. The asuras (demons) grasped Vasuki firmly by the head, while the devas (gods) took their position at his tail, each side pulling with immense force in this grand, divine endeavor. –(Mahabharat, Adiparva)

With great pain, Vasuki endured being pulled back and forth, vomiting poison and withstanding agony—all for the well-being of the universe. From this divine act emerged the Amrita, the nectar of immortality, along with celestial gems, beings, and Lakshmi herself.

Vasuki’s contribution, while painful, was pivotal to the cosmic order.

A Plea for Mercy and a Prophecy of Hope

After the churning, Vasuki, along with other cursed serpents and the devas, approached Brahma. They bowed and pleaded, telling him of Kadru’s curse and the fiery sacrifice destined to wipe out their kind.

Brahma listened.

And then he spoke words that would echo through time:

“Do not fear. A savior shall be born. From parents who both bear the name ‘Jaratkaru,’ a child of wisdom and virtue will arise. He alone shall stop the destruction and rescue the righteous among you. But only those among you who perform good deeds shall be spared.”

Hope flickered.

And so the serpents waited.

The Forest Encounter: Jaratkaru and the Suffering Ancestors

In a thick forest, where sunlight barely kissed the earth, an elderly ascetic named Jaratkaru was wandering alone. One day, he came across a surreal and haunting vision:

A group of frail, ghostly men were hanging upside down from a tree, suspended by a single thread of grass, their heads dangling over a yawning pit.

Moved by the sight, the sage asked who they were.

Their answer stunned him:

“We are your ancestors, O Jaratkaru. Because you have taken the path of renunciation and have no offspring, no one performs our ancestral rites. We are doomed to this torment.”

The sage was shaken. Despite his vow of celibacy, he offered them hope. “I shall marry,” he declared, “but only if I find a woman who shares my name. And I shall not bear the burden of her upkeep.”

The Serpent Princess: Jaratkaru Meets Jaratkaru

Fate smiled.

In the kingdom of serpents, Vasuki had a sister named Jaratkaru—a maiden as wise as she was noble. Vasuki brought her to the sage and agreed to his conditions.

Thus was forged a most unusual union: a human sage and a serpent princess, joined in destiny and prophecy.

From this marriage was born a child—a child destined to stop a fire that could consume the world.

अस्तीत्युक्त्वा गतो यस्मात् पिता गर्भस्थमेव तम् । वनं तस्मादिदं तस्य नामास्तीकेति विश्रुतम् ।।

-The child was still in his mother’s womb when his father, Sage Jaratkaru, departed once again for the forest. As he left, he uttered a single word — “Asti” — meaning “he exists.” From that word, the child came to be known as Astika, and by that name, he became renowned throughout the world.

-Mahabharat, Astikparva

Astika’s Youth: The Fire Within

Raised under the guidance of Sage Chyavana, Astika was no ordinary boy. He mastered the Vedas and shone like fire in his intellect and spirit. His presence brought peace; his words commanded attention.

But as Astika grew, so did the storm brewing in the royal halls of Hastinapur.

The Tragedy of King Parikshit and the Rise of Janamejaya

King Parikshit, the grandson of Arjuna, once insulted a meditating sage by placing a dead snake around his neck. The sage’s son, enraged, cursed him:

“You shall die in seven days, bitten by the serpent Takshaka.”

And so it happened.

Takshaka, the mighty naga, bit Parikshit, killing him instantly.

The king’s son, Janamejaya, was devastated—and vengeful. He swore vengeance not just on Takshaka, but on the entire serpent race.

The Sarpa Satra Begins: A Yagna of Vengeance

Janamejaya summoned his priests and began the Sarpa Satra—an immense ritual meant to annihilate every serpent on earth.

Priests chanted mantras that pulled serpents into the sacrificial fire. Millions of snakes—innocent and guilty alike—were dragged screaming into the flames.

Takshaka, fearing for his life, sought refuge in Indra’s heavenly palace.

But Janamejaya’s priests invoked a terrifying mantra:

“Indraya Takshakaya Swaha!”

Even Indra couldn’t withstand the power of the ritual. He fled, abandoning Takshaka, who began falling toward the fire.

The serpent race teetered on the edge of extinction.

Astika Intervenes: The Boy Who Stopped the Fire

Just as Takshaka was about to fall into the flames, Astika arrived.

Draped in humility, his voice calm, he approached Janamejaya and praised his strength, lineage, and righteousness. The king, pleased, offered to grant him a boon.

Astika made a simple request:

“O King, stop the Sarpa Satra.”

A gasp rippled through the court.

But Janamejaya was a man of dharma. Bound by honor and his own promise, he agreed.

The fire died. The chants ended.

The serpent race was saved.

Vasuki’s Blessing and the Power of Remembrance

Vasuki, overwhelmed with gratitude, appeared before Astika and declared:

“Whoever remembers your name, O Astika, shall never be harmed by any serpent.”

यो जरत्कारुणा जातो जरत्कारी महायशाः । आस्तीकः सर्पसत्रे वः पन्नगान् योऽभ्यरक्षत ।

तं स्मरन्तं महाभागा न मां हिंसितुमर्हथ ।।

“He who was born of Jaratkaru and Jaratkaru, the noble Astika who halted the serpent sacrifice – I remember him now. O blessed serpents, do not harm me.”

सर्पापसर्प भद्रं ते गच्छ सर्प महाविष । जनमेजयस्य यज्ञान्ते आस्तीकवचनं स्मर ।।

O venomous serpent, begone! May blessings be upon you—now take your leave. But before you go, remember the vow you made to Astika at the conclusion of King Janamejaya’s great yagna. Honor your word.

आस्तीकस्य वचः श्रुत्वा यः सर्पो न निवर्तते । शतधा भिद्यते मूर्ध्नि शिंशवृक्षफलं यथा ।।

“The serpent who dares not retreat even after hearing Astika’s sacred oath—its hood shall shatter into a hundred pieces, like the bursting pod of a Shisham tree.”

And thus, the Astika mantra was born—an eternal shield passed down through generations.

The Legend in Stone and Bronze: Ancient Sculptural Depictions

This story, rich in symbolism, found its way into art and sculpture across India:

🗿 1. Bengal, 11th Century – Pala Period

This exquisite stone sculpture from the Pala dynasty era (11th century) showcases the serpent princess Jaratkaru, sister of the Naga king Vasuki, seated gracefully upon a lotus throne (kamalasana)—a classic symbol of purity and divine presence in Indian art.

Above her head arches a seven-hooded serpent, forming a protective naga chhatra (serpent canopy), signifying her celestial lineage. In her lap rests a small naga, representing the surviving Naga lineage that was spared from extinction due to her sacrifice and the heroic actions of her son. The small snake bears a nagamani (serpent gem) on its hood—a traditional symbol of power, wisdom, and spiritual awakening.

To her right stands Sage Jaratkaru, shown emaciated with an ascetic’s thin frame, matted hair (jata) tied in a topknot, and a yogapatta (meditation band) strapped around his legs, identifying him clearly as a forest-dwelling renunciate.

To her left stands their son Astika, marked unmistakably by a cobra hood over his head, a symbol of both his divine heritage and his future role as the savior of the serpents.

This composition beautifully captures the triadic power of sacrifice, dharma, and redemption embodied by this legendary family.

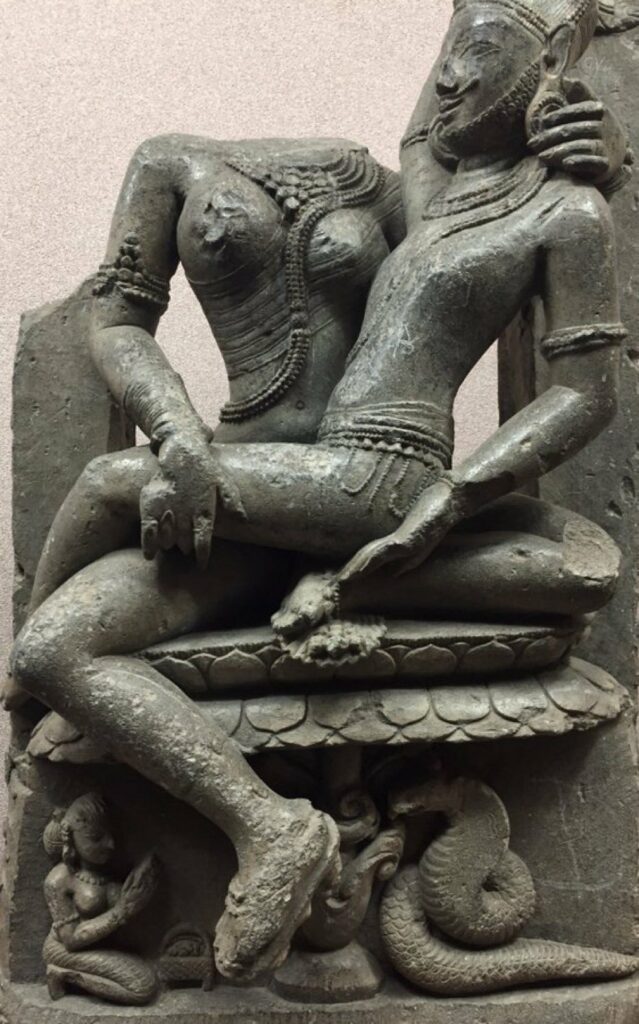

🗿 2. Bhubaneswar, 10th Century

This rare and intimate stone relief from 10th-century Bhubaneswar presents a reversal of typical iconography found in divine or sage depictions.

Here, Sage Jaratkaru, with a well-sculpted beard and moustache, is seen resting on the lap of his wife, the serpent maiden Jaratkaru, who sits serenely upon a lotus pedestal. Her clothing and jewelry are carved in exquisite detail, showcasing the fine craftsmanship of Odisha’s medieval artisans.

Beneath the throne, a devotee is seen making an offering, possibly in a basket, hinting at continued veneration of the naga lineage or the goddess form of Jaratkaru.

To the left of the composition, there is a carved serpent bearing the ‘naganasha’ (serpent destroyer) symbol—perhaps a visual reminder of the threat the Naga race faced during Janamejaya’s serpent sacrifice.

The unique reversal in this sculpture—where the sage rests on the lap of his wife rather than the common iconography of goddesses resting on male deities—is a striking expression of feminine grace, support, and the equality (or even primacy) of spiritual strength in the female figure. This inversion is both rare and symbolically powerful.

🗿 3. Bronze Kamandalu, Bihar

This bronze kamandalu (water vessel) from Bihar is a masterpiece of metalcraft and storytelling. Crafted with exquisite detail, the vessel features finely carved figures of Jaratkaru (the sage), Jaratkaru (the serpent maiden), and their son Astika—collectively presented as “Jaratkaru and Sons”, in a composition that fuses familial unity with divine mission.

The miniature reliefs are rendered with astounding precision—from the texture of clothing to the expressions on their faces. Despite the small scale, the artists have managed to convey layered meanings and emotion through posture, symbolism, and proportion.

This artifact stands as a testament to the refined artistic sensibilities of early medieval Bihar, and to the reverence this myth commanded in religious and household contexts.

To behold such an object is to stand in awe not only of its beauty but of the ancestral devotion and mythological memory it enshrines in every curve.

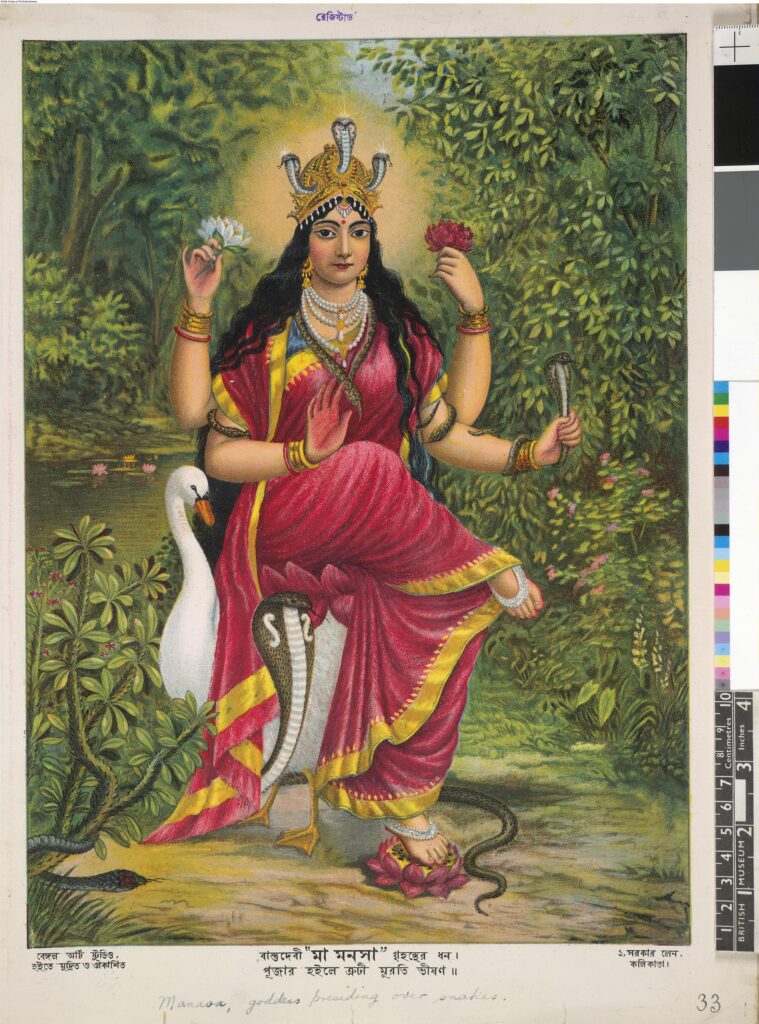

From Serpent Princess to Goddess: The Rise of Manasa Devi

In later centuries, some traditions evolved.

Scholars suggest that Jaratkaru, the serpent princess, became worshipped as Manasa Devi—a goddess who protects against snakebites and grants fertility.

She is still worshipped in Bihar and Bengal, especially during Shravan, when the monsoon brings snakes into the open.

Did You Know? Mahabharata Was First Narrated at This Yagna

A little-known fact: The Sarpa Satra yagna where Astika stopped the fire was also where Sage Vaishampayana first narrated the Mahabharata to King Janamejaya.

Thus, from the flames meant to destroy life came forth India’s greatest epic.

Conclusion: The Eternal Legacy of Astika

The legend of Astika is not just a myth—it is a mirror reflecting themes of compassion, destiny, dharma, and redemption. It reminds us that even in a world driven by vengeance, a single voice of reason and courage can halt destruction.

So the next time you hear the mantra whispered:

“Astika, born of Jaratkaru and Jaratkaru, protector of serpents – I remember him now…”

…know that you’re echoing a tale that once saved a race, stopped a fire, and changed the fate of the world.

References:

1. Mahabharat Volume 1, Geeta Press, India.

2. Mohapatra, Ratnakar. “Iconography of Fifteen Sculptures from the Khordha District of Odisha.” ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, KISS Deemed to be University, https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v[n].i[n].[ArticleID].