The Mahabharata is filled with heroic figures whose stories are celebrated openly like Bhishma, Arjuna, Krishna. But there is one character without whom Bhishma’s fall would not have been possible, and yet the memory of that character remains strangely faint in popular culture and even in temple art. That character is Shikhandi.

From an Indology perspective, Shikhandi is far more than a supporting warrior. Shikhandi is the turning point—an instrument of destiny shaped by revenge, divine boons, gender transformation, and political crisis. What makes this story even more fascinating is that Shikhandi’s presence is not limited to literature. Rarely, Shikhandi appears in sculpture, most notably near Pune at Bhuleshwar, and astonishingly, on a Khmer Hindu Pyramid in Cambodia.

This blog traces the complete connected arc: from Amba to Shikhandi, from Kurukshetra to Cambodia, while keeping the story intact and historically meaningful.

Amba’s Humiliation: The Origin of Shikhandi’s Revenge

To understand Shikhandi, we must begin with Amba. Amba’s story is not simply tragic romance. It is the psychological foundation of one of the most intense revenge arcs in Indian epic tradition.

Amba was wronged and humiliated due to Bhishma’s actions, and her life was pushed into a dead-end by decisions she never consented to. When she sought justice, she discovered a harsh reality: Bhishma was not easily punishable, not even by legends. Even Parashurama, one of the most formidable warriors, could not defeat Bhishma.

This realization changes Amba’s path completely. If nobody else could defeat Bhishma, then she would have to become the force that brings him down. She began an extremely severe tapasya (penance) with only one purpose: revenge.

सा नदी वत्सभूम्यां तु प्रथिताम्बेति भारत । वार्षिकी ग्राहबहुला दुस्तीर्था कुटिला तथा ।।

सा कन्या तपसा तेन देहार्धेन व्यजायत । नदी च राजन् वत्सेषु कन्या चैवाभवत् तदा ।।

-After a period of intense austerity, Princess Amba was transformed by the power of her penance into the river known as Amba in the kingdom of Vatsa. This river flowed only during the rainy season and was inhabited by numerous crocodiles, making descent into its waters for bathing or the performance of religious rites extremely difficult. Its course was markedly winding. Through the same ascetic power, Amba assumed a dual manifestation: with one half of her body she became the river Amba, while with the other half she was reborn as a maiden in the land of Vatsa.

As the story goes, her tapasya became so fierce that half her body reflected in the river, and from that reflection a girl-child emerged. In that form too, she continued the penance. Ultimately, Trilochana Shiv appeared, pleased with her austerities. He granted her a decisive boon: she would be born as a woman in a king’s lineage and become the cause of Bhishma’s destruction.

After receiving this boon, that girl entered the fire (agnipravesh). But the fire did not end the vow. It only carried it forward.

Drupada’s Boon and Shikhandi’s Birth: The Secret Prince of Panchala

At the same time, in Panchala, King Drupada was performing penance for the continuation of his dynasty. Mahadeva appeared before him too and granted a mysterious boon: Drupada would receive a daughter, but in time, she would take male form and carry the lineage forward.

अपुत्रस्य सतो राज्ञो द्रुपदस्य महीपतेः । यथाकालं तु सा देवी महिषी द्रुपदस्य ह ।।

कन्यां प्रवररूपां तु प्राजायत नराधिप । अपुत्रस्य तु राज्ञः सा द्रुपदस्य मनस्विनी ।।

ख्यापयामास राजेन्द्र पुत्रो ह्येष ममेति वै ।ततः स राजा द्रुपदः प्रच्छन्नाया नराधिप ।।

पुत्रवत् पुत्रकार्याणि सर्वाणि समकारयत् । रक्षणं चैव मन्त्रस्य महिषी द्रुपदस्य सा ।।

चकार सर्वयत्नेन ब्रुवाणा पुत्र इत्युत । न च तां वेद नगरे कश्चिदन्यत्र पार्षतात् ।।

-At the destined time, Drupada’s queen—childless for years—gave birth to a daughter of striking beauty. Yet because she desperately wanted a son, she immediately announced that the baby was a boy. From that moment, Drupada quietly carried out every ritual exactly as one would for a prince. The queen worked relentlessly to ensure the truth never surfaced. She consistently referred to the child as her son, and the secret was maintained so effectively that across the entire city no one knew the child was a girl—except Drupada himself.

When the child was born, it was a daughter. But Drupada kept this as a secret within the palace. The child was publicly treated as a son and raised like a prince. The name given was Shikhandi.

This is one of the most important details of Shikhandi’s character. Shikhandi was not raised with feminine restrictions. Shikhandi was trained in administration, royal duties, and most importantly, warfare. Over time Shikhandi became highly skilled in martial training and war strategy, a detail that later becomes critical in Kurukshetra.

Shikhandi’s Marriage Crisis: When a Personal Truth Became a National Threat

ततो राजा द्रुपदो राजसिंहः सर्वान् राज्ञ कुलतः संनिशाम्य । दाशार्णकस्य नृपतेस्तनूजां शिखण्डिने वरयामास दारान् ।।

हिरण्यवर्मेति नृपो योऽसौ दाशार्णकः स्मृतः । स च प्रादान्महीपालः कन्यां तस्मै शिखण्डिने ।।

-After this, King Drupada, the greatest among the kings, reviewed the lineage and background of every royal family. He then chose the daughter of Dasharnaraja for Shikhandi. The king of Dasharna was Hiranyavarma, and he gave his daughter to Shikhandi in marriage.

Drupada arranged Shikhandi’s marriage to the daughter of King Hiranyavarma. This alliance was meant to strengthen political ties, but it produced the biggest crisis of Shikhandi’s life. After marriage, the truth could not remain hidden. The princess realized Shikhandi’s biological reality and informed her father.

Hiranyavarma did not see it as fate or divine complexity but he saw it as deception. He became furious and began mobilizing a massive army, preparing to attack Panchala. A personal identity issue had now become a geopolitical threat.

Shikhandi, seeing that her existence had placed Drupada and Panchala in danger, left the city in guilt and grief, withdrawing into a forest to perform penance.

The Yaksha Exchange: How Shikhandi Obtained Male Form

In the forest, Shikhandi reached a deserted palace belonging to a Yaksha named Sthunakarna. Seeing Shikhandi’s suffering, the Yaksha offered compassion in the form of a miraculous exchange. He granted Shikhandi his masculinity for some time and took Shikhandi’s femininity, with the condition that the exchange would later be reversed.

Yaksha spoke,

प्रभुः संकल्पसिद्धोऽस्मि कामचारी विहङ्गमः । मत्प्रसादात् पुरं चैव त्राहि बन्धूंश्च केवलम् ।।

स्त्रीलिङ्गं धारयिष्यामि तदेवं पार्थिवात्मजे । सत्यं मे प्रतिजानीहि करिष्यामि प्रियं तव ।।

-I am resolute and powerful, free to move wherever I wish, even through the sky. By my grace, you will be able to protect your city and your people. Princess, I will take on your feminine form for now. But when your work is done, promise me solemnly; that you will return my masculinity to me. Only then will I help you achieve what you seek.

With this boon, Shikhandi returned in male form and confronted the political crisis directly. Shikhandi explained the full story to Hiranyavarma, and the war was avoided. Panchala was saved.

But the larger destiny had only begun to assemble itself. Because Shikhandi’s transformation was not merely to solve a marriage problem. It was the final step needed for Kurukshetra.

Shikhandi at Kurukshetra: The Reason Bhishma Fell

On the Tenth Day, Bhishma thought,

शक्तोऽहं धनुषैकेन निहन्तुं सर्वपाण्डवान् ।यद्येषां न भवेद् गोप्ता विष्वक्सेनो महाबलः ।।

(अजय्यश्चैव लोकानां सर्वेषामिति मे मतिः ।) कारणद्वयमास्थाय नाहं योत्स्यामि पाण्डवान् ।।

अवध्यत्वाच्च पाण्डूनां स्त्रीभावाच्च शिखण्डिनः ।पित्रा तुष्टेन मे पूर्व यदा कालीमुदावहम् ।।

स्वच्छन्दमरणं दत्तमवध्यत्वं रणे तथा । तस्मान्मृत्युमहं मन्ये प्राप्तकालमिवात्मनः ।।

-“If Lord Krishna had not protected the Pandavas, I could have destroyed them all with just one bow. God is invincible across all worlds. But today, I will not fight the Pandavas; and there are two reasons for this. First, they are the sons of Pandu, and I cannot strike them down. Second, Shikhandi, who was once a woman, now stands before me.

Long ago, when I arranged my mother Satyavati’s marriage to my father, he granted me two boons in gratitude: that I would die only when I wished, and that no one would be able to kill me in battle. Therefore, I must now accept death by my own choice. I feel that moment has finally come.”

At Kurukshetra, Bhishma was nearly invincible. He possessed icchamrityu, the boon of choosing his death. More importantly, his military prowess was unmatched. Even the Pandavas struggled to imagine victory as long as Bhishma stood as the Kaurava commander.

That is where Shikhandi became decisive.

Bhishma had vowed not to raise weapons against a woman. Even though Shikhandi now appeared male, Bhishma considered Shikhandi to be female due to Shikhandi’s origin as Amba’s rebirth. Therefore, in battle, Bhishma refused to attack Shikhandi.

Shikhandi stood as a shield. With Shikhandi placed in front, Arjuna attacked freely. Bhishma did not counter with full force, and Arjuna’s arrows struck relentlessly until Bhishma collapsed onto the famous bed of arrows.

Thus, Shikhandi became the direct cause; whether morally or strategically behind Bhishma’s fall.

This is why, in any serious reading of the epic, Shikhandi is not a side character. Shikhandi is a mechanism of dharma, fate, and revenge.

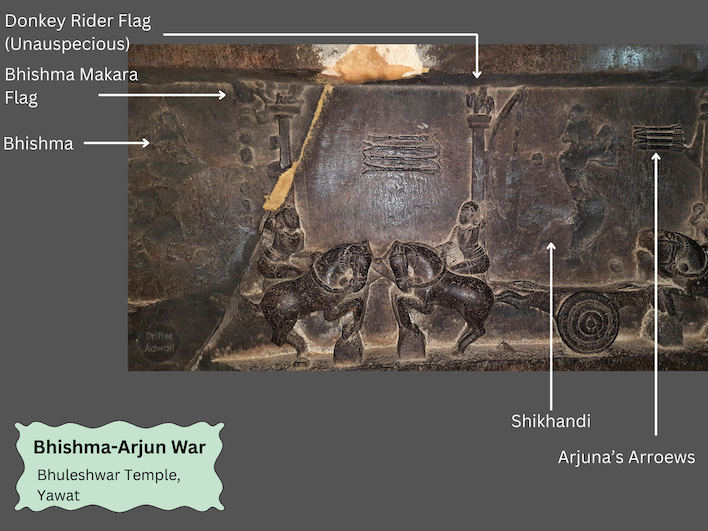

Shikhandi in Indian Temple Art: The Rare Sculpture at Bhuleshwar

Despite Shikhandi’s crucial role, Shikhandi sculptures are extremely rare in India. This may be because the story is uncomfortable for conventional heroic storytelling. It deals with transformation, identity, revenge, and moral ambiguity.

However, a notable example survives near Pune at the Bhuleshwar temple, an ancient Shiva temple often dated around the early medieval period. Here, in the Bhishma-Arjuna battlefield depiction, Shikhandi appears in the center.

How do we identify Shikhandi? Through the banner (dhvaja) motif: a man riding a donkey. The Mahabharata’s description of Shikhandi’s banner is considered inauspicious or “abhadra,” matching this identifying symbol.

Though the sculpture is damaged, its presence is astonishing. It tells us that medieval Indian temple artists did recognize Shikhandi’s epic importance.

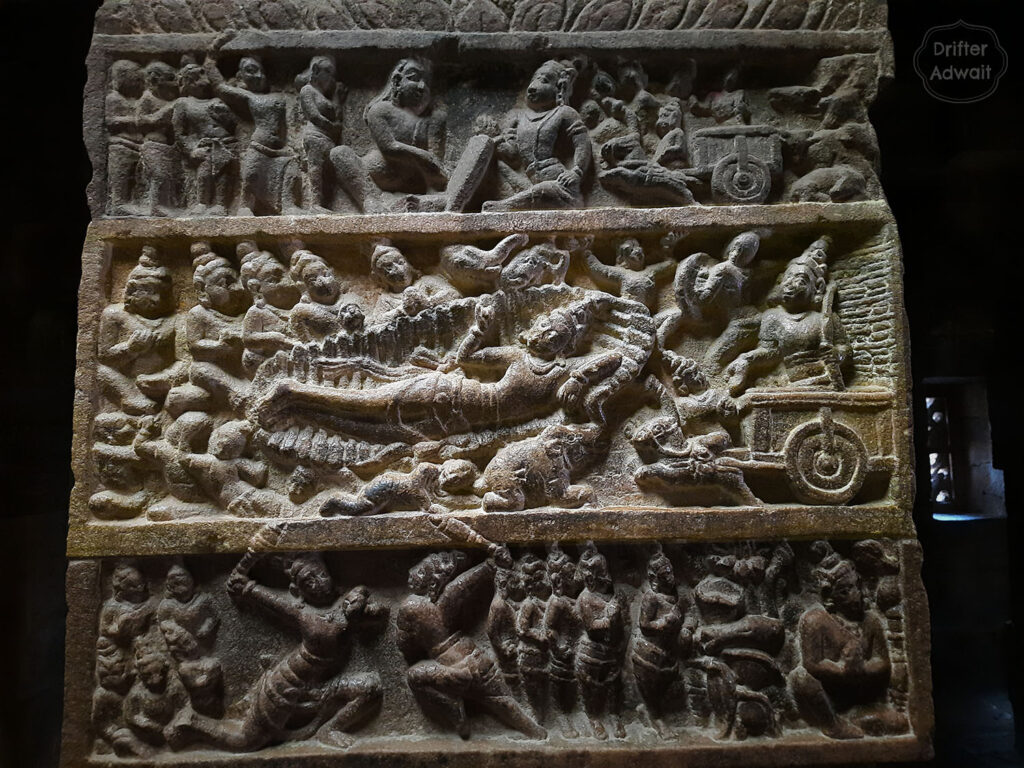

Shikhandi in Cambodia: The Baphuon Sculpture and the Khmer Mahabharata

Even more surprising is the second major Shikhandi sculpture. Far away in Cambodia, on the Hindu pyramid-temple known as Baphuon.

This is roughly 5,000 km from Maharashtra. Yet the same epic scene is carved there: Bhishma versus Arjuna, with Krishna as Arjuna’s charioteer. In this depiction, Shikhandi is shown in front, attacking Bhishma, wearing Khmer-style attire.

This is not random decoration. It is a cultural statement.

The Khmer civilisation did not merely import Indian stories as entertainment. They absorbed the philosophy. They understood that the Mahabharata is not a victory story. It is an ethical warning system.

Therefore, Shikhandi is carved not as an “ideal hero” but as a moral symbol.

Why Did Khmer Artists Choose Shikhandi?

This becomes the deepest Indological question: if temple art is selective, then why carve Shikhandi, a character rarely celebrated even in India?

Because Khmer temple sculpture was not meant to glorify characters. It was meant to instruct kings and society.

The Khmer state ideology relied heavily on the Devaraja concept, where kings were divine representatives. For such a political structure, the Mahabharata becomes a cautionary mirror: when ego, revenge, and rigid vows pretend to be dharma, the kingdom suffers.

Shikhandi’s story is precisely that warning.

Shikhandi does not win the war. Shikhandi makes the war unavoidable.

The Baphuon Shikhandi is not a statue of pride. It is a carved reminder that revenge travels through births, identities, and nations. Until it consumes everything.

Shikhandi’s End: Revenge Always Finds Its Way Back

The Mahabharata does not romanticize Shikhandi’s victory. Even after Bhishma’s fall, peace does not arrive for Amba’s soul.

Ashwatthama, blinded by revenge for his father’s death, attacks the Pandava camp at night. In this brutal assault, Shikhandi becomes a victim. The text emphasizes cruelty: Shikhandi’s body is cut into pieces.

ततो भीष्मनिहन्ता तं सह सर्वैः प्रभद्रकैः । अहनत् सर्वतो वीरं नानाप्रहरणैर्बली ।।

शिलीमुखेन चान्येन ध्रुवोर्मध्ये समार्पयत् । स तु क्रोधसमाविष्टो द्रोणपुत्रो महाबलः ।।

समासाद्य द्विधा चिच्छेद सोऽसिना।।

-Thereafter, the mighty Bhishmahanta Shikhandi along with all the Prabhadras started attacking Ashwatthama from all sides with various types of weapons. With an arrow Shikhandi hit Ashwatthama between his two eyebrows. Then the mighty son of Drona, in a fit of anger, approached Shikhandi and cut him into two pieces with his sword.

This is the Mahabharata’s final statement on revenge:

Those who live by revenge ultimately end by it.

Shikhandi’s story is not a glory tale. It is an unease tale. It doesn’t celebrate dharma’s triumph—it shows revenge’s cost.

Final Thoughts: Shikhandi as a Mirror, Not a Hero

Western philosophy often says revenge is best served cold. Measured, delayed, precise. The Mahabharata offers a darker truth. It does not praise revenge at all. It dissects it.

Through Shikhandi, Bhishma, and Ashwatthama, the epic shows that revenge never resolves anything. It only moves by wearing new faces, creating new wars, and leaving behind destruction disguised as justice.

That is why Shikhandi matters. Not because Shikhandi is a flawless hero, but because Shikhandi is a mirror. For individuals, for kings, for civilizations. Perhaps that is exactly why Khmer artists carved Shikhandi into stone. They do not display victory, but they do preserve the reason behind collapse.

References:

1. Mahabharata Volume 1,3, Geeta Press Gorakhpur, India.

2. Kanitkar, Kumud. “Mahābhārata Panels in the Bhuleshvara Temple near Yavat.” Jnanapravaha , vol. XX, 2017.

Interested to know more such nuances about Mahabharata? Try our Mahabharata Quiz Right Here…