Ancient India offers not just treasures of art and monuments but enduring testimonies to ethical governance. Among these, the Sohgaura Copper Plate—India’s oldest copper plate inscription—shines as a profound symbol of state responsibility, welfare, and foresight. This humble artifact contrasts starkly with two other infamous famines in Indian history, those under British colonial and Mughal rule. Through an Indological lens, the copper plate reveals the essence of Rajadharma, the moral duty of rulers toward their people.

Introduction: Famines as the Mirror of Civilization

History is not remembered only through victories and monuments. Civilizations reveal their true soul in times of famine—when the earth withholds its rain, when crops fail, and when hungry mouths look up to their rulers. In such moments, the mask of power slips away, and the true face of kingship emerges.

India has witnessed many famines. Among them, three stand as stark markers of what rulers chose to do when hunger swept the land:

1. The Bengal Famine of 1943 under Winston Churchill’s British Raj.

2. The Mughal Famine of the 17th century, when Shah Jahan chose marble over men.

3. The Ancient Mauryan Famine, remembered through the Sohgaura Copper Plate inscription, the oldest copper plate inscription in India.

This journey across time is not merely about hunger. It is about Rajadharma, the ancient Indian philosophy of righteous rule, which saw the king as the father and the subjects as his children.

The Bengal Famine of 1943: Churchill’s Brutality and Colonial Arrogance

The Second World War was at its height. Europe burned as nations fought for supremacy. In India, cyclones and floods devastated Bengal’s farmlands. Crops failed. To make matters worse, Burma—the rice bowl of the region—was lost to the Japanese. Grain supplies shrank, and famine swept the land.

This was the moment for the British Raj to protect its “subjects.” But instead of sending aid, Churchill’s government diverted Indian grain to Europe. Millions in Bengal were left to starve.

When British officials requested relief shipments, Winston Churchill infamously mocked the victims:

“I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.”

He went further:

“Relief would do no good. Indians breed like rabbits and will outstrip any available food supply.”

The result was catastrophic: over 3.5 million Indians perished in one of the deadliest man-made famines in history. Children starved while ships carried grain past Bengal’s shores to feed distant warfronts.

This famine was not just about rice. It was about the colonial mindset that saw Indians as expendable. It revealed the utter absence of Rajadharma in imperial rule.

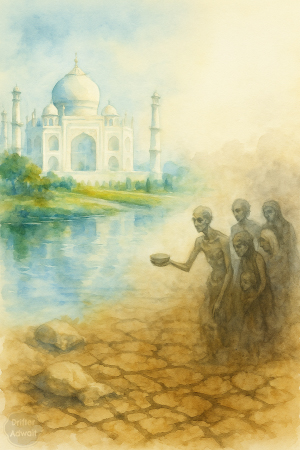

The Mughal Famine of the 17th Century: Taj Mahal Amid Starvation

Travel back three centuries earlier. Failed monsoons struck India in the 17th century, and for three years, no crops grew. Hunger spread across the Mughal empire, and about 3 million people died.

What did Emperor Shah Jahan, the mighty Padshah, do? Instead of channeling the royal treasury to famine relief, he poured it into building a tomb for his beloved wife—the Taj Mahal.

Extra taxes were levied upon the already starving subjects. Precious marble was polished while fields lay barren. Laborers toiled for a monument, even as the people around it withered away.

The Taj Mahal, often celebrated as a wonder of the world, was born not only from love but also from hunger. It stands as a monument to misplaced priorities—a symbol of vanity erected on the graves of millions.

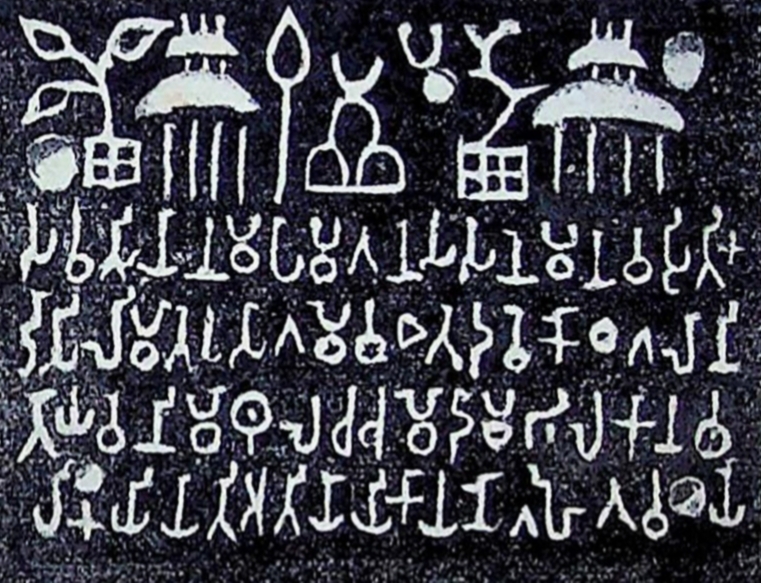

The Sohgaura Copper Plate: India’s Oldest Copper Plate Inscription

Now, let us journey even further back—over two millennia ago, to the Mauryan Empire. Near the Rapti River in Uttar Pradesh lies a small village called Sohgaura. Here, archaeologists discovered something extraordinary: a copper plate inscribed in Brahmi script.

This Sohgaura copper plate inscription is India’s oldest known copper plate. Its subject? Not conquest. Not monuments. But famine relief.

The copper plate bears these words

The Brahmi Script Inscription:

𑀲𑀸𑀯𑀢𑀺𑀬𑀸𑀦𑀁 𑀫𑀳𑀸𑀦𑀁 𑀲𑀸𑀲𑀦𑁂 𑀫𑀸𑀦𑀯𑀸𑀲𑀺𑀢𑀺𑀓 𑀟𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀺𑀫𑁂𑀢𑁂

𑀉𑀲𑁆𑀲𑀕𑀸𑀫𑁂 𑀯 𑀏𑀢𑁂 𑀤𑀼𑀯𑁂 𑀓𑁄𑀝𑁆𑀞𑀸𑀕𑀸𑀮𑀸𑀦𑀺 𑀢𑀺𑀦-

𑀬𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀺 𑀫𑀁𑀣𑀼𑀮𑁆𑀮𑁄𑀘-𑀙𑀫𑁆𑀫𑀸-

𑀤𑀸𑀫-𑀪𑀸𑀮𑀓𑀸𑀦𑁆𑀯 𑀮𑀁 𑀓𑀬𑀺𑀬𑀢𑀺 𑀅𑀢𑀺𑀬𑀸𑀬𑀺𑀓𑀸𑀬 𑀦𑁄 𑀕𑀳𑀺𑀯𑁆𑀯𑀸𑀬

Transliteration:

Sāvatiyānaṁ mahāmattānaṁ sāsane mānavāsitike ḍasilimete ussagāme va ete duve koṭṭhāgālāni tina-yavāni maṁthulloccha-chammā-dāma-bhālakaṁva laṁ kayiyati atiyāyikāya no gahivvāya.

Translation: “From the camp at Shravasti, the order of the Mahamatras: If famine is apprehended, the storehouses at Triveni, Mathura, Chanchu Modama, and Bhadra are to be opened. These depots exist for distribution among the people. In distress, they must not be withheld.”

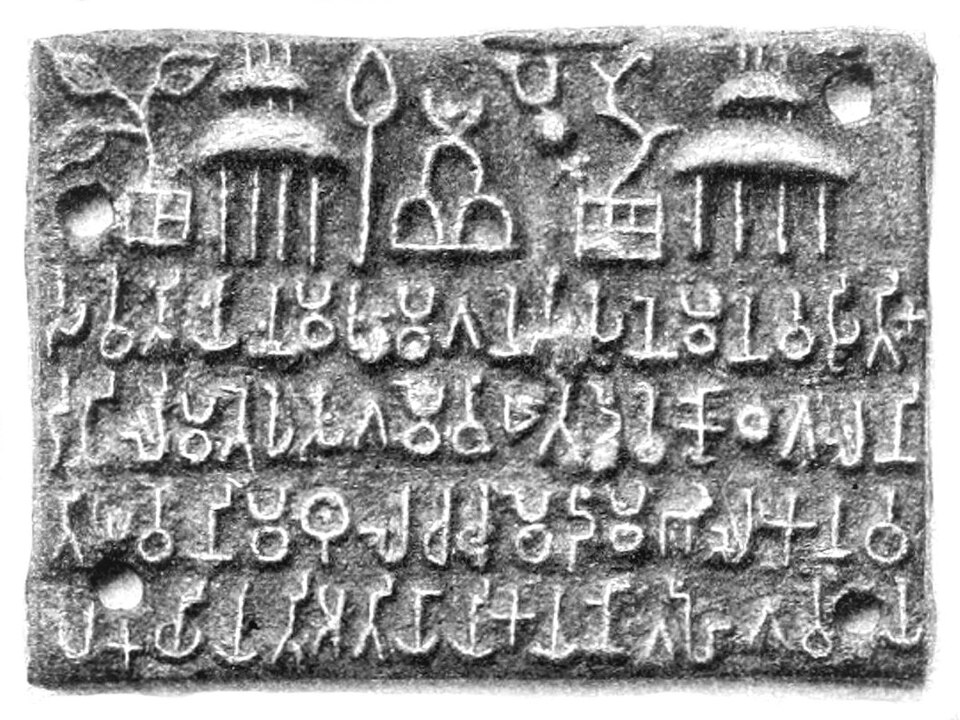

Symbols on the Sohagaura Copper Plate

The Sohgaura copper plate also carries pictorial symbols, so even the unlettered could understand:

A three-leafed tree within an enclosure → prosperity or Symbol of Tryavani.

A granary with a spoon or laddle beside it → food storage/Chaitya or Mount Meru.

A leafless tree → famine/Location or Tree of Chanchu.

Another granary symbol → relief in scarcity.

Above the granary → ४ → NandiPada

The Mauryan royal emblem of three hills topped by a crescent moon → authority and responsibility.

These images told a story: even if famine struck, the king’s grain stores would feed the people. It was a public assurance, a visual contract between ruler and subject.

Craftsmanship of the Sohgaura Copper Plate

One of the most intriguing details about the Sohgaura Copper Plate is how it was actually made. The Indologist Dr. Hoernle, while studying the inscription, noticed tiny dot-like projections between some of the Brahmi letters. From this, he concluded that the plate was not engraved by hand in the usual way, but cast in a mould of sand, which was slightly rough.

This discovery tells us something extraordinary: the plate may not have been a one-off artifact, but part of a system where multiple identical copies were produced from the same mould and distributed across different villages and administrative centers. In other words, this famine-relief order was not meant for a single location but was a standard directive of the Mauryan administration, ensuring that officials everywhere had clear instructions to release grain from state granaries during times of scarcity.

Strategic Placement of Granaries near the Rapti River

The historian Prof. Barua went a step further and tried to reconstruct the geography implied by the inscription. He suggested that the two storehouses mentioned in the Sohgaura Copper Plate were likely built on opposite banks of the Rapti River. This was no accident. Just as in pre-colonial India the Indian Kings often built Dharamshalas (public rest-houses) on both sides of long river crossings, the Mauryan state probably followed a similar system for its famine-relief granaries.

According to Barua, one granary was placed on the western bank of the Rapti, at the junction where the roads from Mathura and Chanchu converged, while the second granary stood across the river where the road continued toward Tryavani. This thoughtful arrangement meant that people on both sides of the river—whether villagers or travelers—had equal access to food relief during a crisis. It also shows how Mauryan planners integrated geography, infrastructure, and public welfare into a single administrative vision.

Ancient Indian Granaries and Their Architecture

The Sohgaura Copper Plate does not just record famine relief in words—it also depicts granary-like structures. These buildings are shown with double roofs and four frontal posts, details that fascinated the scholar George Grierson. He compared them to the landlords’ granaries still found in Bihar (especially in Gaya district), where rent was often collected in kind. Even in the 19th century, such grain stores were built with double roofs for ventilation, exactly like the designs carved on the copper plate.

Grierson further pointed out that the four visible posts may have been an early attempt at perspective, with the engraver trying to represent both the front and rear posts in a two-dimensional drawing. These details reveal two things: first, that the Mauryan state took architectural accuracy seriously when communicating famine policies, and second, that they designed inscriptions in such a way that even illiterate villagers could recognize the granaries and understand that food would be made available in times of scarcity.

Rajadharma in Ancient India

The Sohgaura copper plate inscription is a living example of Rajadharma—the king’s duty toward his people. Unlike Churchill’s disdain or Shah Jahan’s vanity, the Mauryan ruler treated his subjects as his own family.

In Indian thought, the king was not a master but a guardian. This ethos echoed from the Rigveda’s prayers for food for all beings, to the Mauryan granaries, to Shivaji Maharaj’s strict orders centuries later: “Do not touch even the stalk of the peasant’s vegetables.”

This continuity shows that compassion, not exploitation, was the cornerstone of Indian polity.

Comparing the Three Famines: Foreign Rule vs. Indigenous Dharma

Winston Churchill (1943): mocked starving millions, diverted grain, and called Indians “beastly.”

Shah Jahan (17th c.): taxed a starving population to build the Taj Mahal.

Mauryan Ruler (3rd c. BCE): built public granaries and issued standing orders for famine relief, carved visibly for all to see.

This contrast is the heart of the matter. Foreign rulers saw India as a body to be drained. Indigenous rulers, bound by Rajadharma, saw India as a family to be nurtured.

Conclusion: The Soul of the Sohgaura Copper Plate

The Sohgaura copper plate, India’s oldest copper plate inscription, is not just a relic. It is a reminder of what true kingship means. It tells us that greatness does not lie in monuments of marble or conquests of empire, but in the simple act of ensuring that no child goes to bed hungry.

When we study this plate, we are not only looking at bronze and Brahmi script. We are looking at the soul of Indian civilization—a civilization where Rajadharma demanded that the ruler protect, nourish, and serve his people as his own children.

This is the true wonder of India—not the Taj, not the Empire, but the copper plate of Sohgaura.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about the Sohgaura Copper Plate

1. What is the Sohgaura Copper Plate?

The Sohgaura copper plate is the oldest known copper plate inscription in India, discovered near the Rapti River in Uttar Pradesh. It dates back to the Mauryan period (3rd–2nd century BCE) and records famine relief measures. Unlike later copper plates used for land grants, this inscription focuses on public welfare and Rajadharma.

2. Why is the Sohgaura Copper Plate important?

It is important because it shows how ancient Indian rulers took proactive steps to protect their people during famines. The plate contains instructions for opening public grain stores during scarcity, making it a rare administrative record of famine relief in ancient India.

3. In which script is the Sohgaura Copper Plate written?

The inscription is written in Brahmi script, one of the earliest writing systems of India. It also contains pictorial symbols like trees, granaries, and spoons, so that even illiterate villagers could understand its meaning.

4. Who issued the Sohgaura Copper Plate inscription?

Scholars debate whether it was issued under Chandragupta Maurya or a later Mauryan ruler, possibly after Ashoka. What is certain is that it reflects Mauryan statecraft and Rajadharma, with officials (Mahamatras) ordered to distribute grain during famine.

5. What does the Sohgaura Copper Plate tell us about ancient India?

It shows that Indian kingship was rooted in dharma and compassion. While later foreign rulers like the British and Mughals neglected famine victims, Mauryan India created granaries and issued standing orders for relief. The plate proves that public welfare was central to Indian polity more than 2200 years ago.

6. Which is the oldest copper plate inscription in India?

The Sohgaura copper plate is the oldest copper plate inscription found in India. Unlike later copper plates used for land grants (such as those of the Gupta period), this inscription is unique because it deals with famine relief and public welfare.

References-

1. G. A. Grierson, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (Jul., 1907), pp. 683-685

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41688160

2. J. F. Fleet, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (Jul., 1907), pp. 509-532 (25 pages) https://www.jstor.org/stable/25210446

3. पुराभिलेखविद्या- शोभना गोखले, मिहाना पब्लिकेशन्स, पुणे.

4. Soghaura inscription. Asiatic Society of Bengal 1865 – Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sohgaura_copper_plate_inscription#/media/File:Soghaura_inscription.jpg

5.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gorakhpur,_Copper_Plate_Edict_Of_Chandragupta_%283rd_century_BCE%29.jpg

6. Willoughby Wallace Hooper: Famine, 1876-78, Bangalore

7. Bengal famine of 1943: Dead and dying children on a Calcutta street published in the Statesman 22 August 1943